Introduction

University President Lee C. Bollinger launched Columbia World Projects in 2017 to bring university research out into the world in the form of projects that tackle some of society’s most intractable problems. His message to the university community was simple:

Aim to be bold and make a significant and lasting difference in people’s lives.

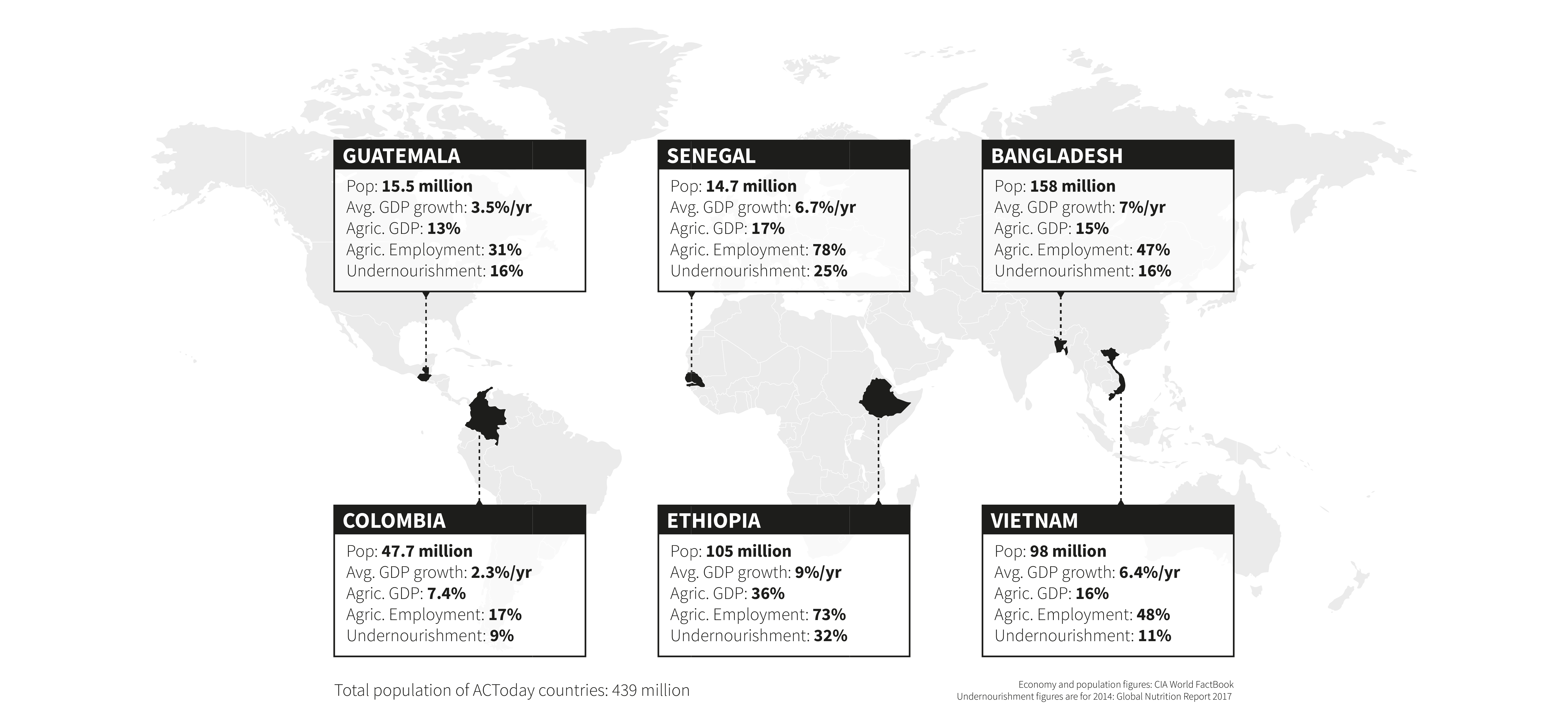

What follows in this report are highlights from the first project to take on President Bollinger’s call to action: Adapting Agriculture to Climate Today, for Tomorrow (ACToday). ACToday is working in six countries— Bangladesh, Colombia, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Senegal and Vietnam—to help meet the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goal 2: ending hunger, achieving food security, improving nutrition and promoting sustainable agriculture. These countries are home to nearly 450 million people, many of whom are chronically undernourished because they depend largely on rainfed agriculture for the food they grow, eat and sell. Ultimately, climate variability is an ever-present threat to their lives and wellbeing.

ACToday is working to improve food security in two ways: by increasing the production and availability of state-of-the-art climate information products and tools, and by improving the way such information is used for decision making, planning and policy related to agriculture and food.

This approach is based on two decades of experience and leadership of Columbia’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI). Since 1996, IRI has implemented science-based solutions for adaptation planning and climate risk management in public health, agriculture and other sectors in more than two dozen countries.

As a Columbia World Project, ACToday works closely with national government agencies and institutions within each country. Our activities also tie into existing programs and goals set forth by our international partners, including, for example, the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), the World Food Program (WFP), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Bank. By working closely with these and other global institutions in the six ACToday countries, we are helping them to better manage climate risks and opportunities across their programs. In this way, we can truly create long-lasting and intergenerational benefits for the millions of people at risk of hunger and malnutrition each year.

We believe the key to ACToday’s success lies in the strength of our external partnerships.

ACToday combines IRI’s knowledge with that of faculty and students from the School of International and Public Affairs, the Earth Institute, the Institute of Human Nutrition and the Center for Sustainable Investment, leveraging their expertise on nutrition, food policy and international development; yet Columbia’s expertise and reach can only take us so far. We believe an essential key to ACToday’s success lies in the strength of our external partnerships.

We’re excited to share some of the accomplishments and hard work of our ACToday country teams and partners.

Lisa Goddard and Walter Baethgen

International Research Institute for Climate and Society

Co-Leads of ACToday

Delivering the Next Generation of Climate Forecasts

In August of 2019, Colombia’s national meteorological service, IDEAM, launched a state-of-the-art climate forecasting system called NextGen. One month later, Guatemala’s weather service, INSIVUMEH, did the same. The launch events were the culmination of nearly two years of collaboration between ACToday and national agencies of both countries.

NextGen is a system for analyzing data, calibrating climate models and verifying forecasts based on a suite of climate tools developed by the International Research Institute for Climate and Society. The new system gives Colombia and Guatemala a powerful upgrade to their forecasting capabilities, and enables them to provide their institutions—and citizens—an unprecedented caliber of climate information for decision making in agriculture, public health and other sectors.

“NextGen is helping us create better forecasts for the actual critical thresholds of interest for the agriculture, water management, health and energy sectors in Colombia.”

Yolanda González Hernández, Director of IDEAM

“We know that in order to make policies and decisions that effectively manage climate risks in their food systems, countries need access to reliable data and the ability to produce skillful forecasts—that’s where NextGen comes in,” said Lisa Goddard, ACToday’s Co-Director. “And under ACToday, we also want to help build the capabilities of national institutions to produce such information locally, using their data and their technical staff. In this way, they become invested in NextGen’s success.”

NextGen allows IDEAM and INSIVUMEH to create forecasts tailored to different sectors, and in a flexible format so that particular climate variables of interest may be assessed.

“For example, imagine you’re a farmer whose maize crop needs at least 90 mm of rainfall around the flowering stage,” said Ãngel Muñoz, who oversees ACToday’s work in Colombia and Guatemala. “It’s important for you to know the likelihood of getting at least that amount. If the probability is low, then you can choose to plant a different crop, or make other farm-level decisions.”

The most common seasonal forecasting systems today provide only the probability of getting “above-normal”, “normal”, or “below-normal” amounts of rainfall for an area, Muñoz said. “But what exactly does that mean for different crops?”

NextGen’s flexible forecast interface allows users to enter any rainfall amount and see what the probability of getting at least that amount for the upcoming growing season is. Users can also calculate the frequency of rainy days, the duration of dry spells, as well as minimum, maximum and mean temperatures.

“NextGen will help make Guatemala a leader in the region when it comes to climate forecasting. This is a historic step forward for the country. It will now be able to provide climate services not just to some, but to all Guatemalans, especially those who depend on rainfed agriculture for food and income,” said ACToday’s Diego Pons, who works on the project’s Guatemala team.

Training Agents of Change: Reaching Ethiopia’s 12 Million Farming Households

Agriculture makes up more than 40% of Ethiopia’s gross domestic product and is the primary source of employment in the country. Nearly all of Ethiopia’s agricultural production happens on smallholder farms (less than three hectares in size) and nearly all of it is rainfed. Every growing season, millions of people bet on having a favorable climate for their crops and livelihoods. A drought, or even small variations in weather and climate conditions during the rainy season, not only threatens the food security of specific communities, but also negatively impacts Ethiopia’s economy.

For this reason, the Ethiopian government was early to recognize the importance of a highly capable national meteorological service to maintain a robust weather network and be able to generate skillful forecasts for the country.

Not too long ago, it used to be that in order to get climate data for a given location in Ethiopia, you’d have to submit a written request… The process would take at least three days. Now it takes three seconds.

Tufa Dinku

With support from IRI’s ENACTS initiative and Data Library, ACToday’s Tufa Dinku worked with the country’s National Meteorological Agency (NMA) since 2010 to completely transform the way in which the agency generates and delivers climate information. Now people can access 40 years of continuous temperature and rainfall data for the whole country at a 4-kilometer resolution.

“Not too long ago, it used to be that in order to get climate data for a given location in Ethiopia, you’d have to submit a written request to the NMA,” said Dinku, who leads ACToday’s work in Ethiopia. “The process would take at least three days. Now it takes three seconds.”

While Dinku recognizes the importance of this achievement, he said it only addressed half of the problem. “We generated this great new climate knowledge for the country. Now it needed to permeate into other parts of the government—ones that are responsible for food policy and decision making.”

Under ACToday, Dinku and the NMA built online mapping and data visualization tools custom-made for staff working in the ministries of agriculture and public health and the country’s disaster management agency. Then they held intensive two-week training courses for these non-climate professionals to learn how to use the new tools.

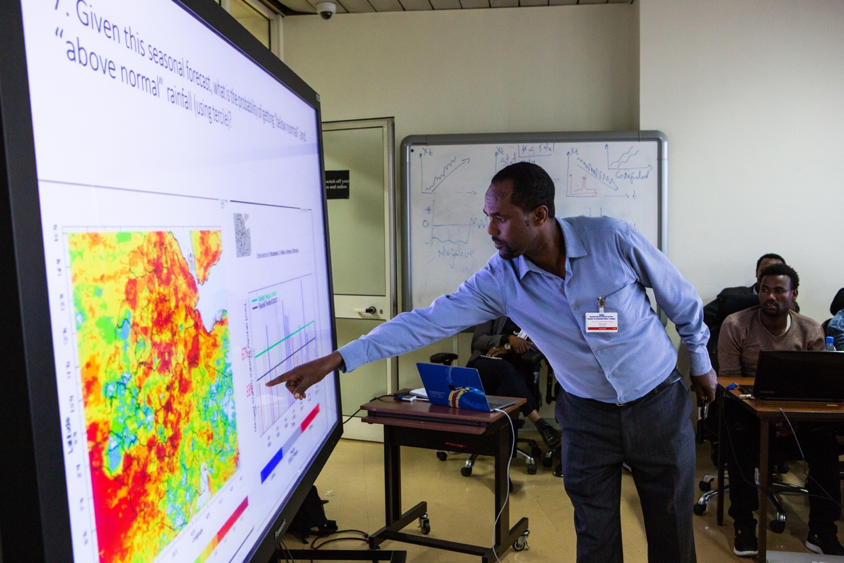

Tufa Dinku, the country lead for Ethiopia, tells his story and describes the efforts of ACToday and the challenges Ethiopia faces in adapting to climate change.

ACToday’s training approach addressed two challenges. The first is that the NMA is a national institution based in the capital, Addis Ababa, but it’s the local level staff in the agriculture sector that need these tools the most. They’re working the closest with farmers. And that’s who NMA invited to take part in the first training.

The other challenge was about scale. No matter how big the NMA is, there’s a limit to how many people it could train to use its services. ACToday’s ultimate goal is to ensure that Ethiopia’s 12 million farming households stand to benefit from better climate information for food security.

“Not only did we train the agriculture staff how to understand and use forecasts, historical climate information and real-time monitoring for their decisions, we trained them to become trainers,” Dinku said.

Eneye Assefa, a crop expert at the Amhara regional agriculture office, was one of the first participants. She had no meteorological knowledge before the training but now has more confidence to advise farmers on what crops will be more productive to plant based on rainfall forecasts.

In the months since the training, Assefa has worked to pass the knowledge she gained to her colleagues in Amhara, as well as those in administrative units below hers. This is exactly what Dinku hoped would happen—that the participants go back to their respective regions and propagate the training and use of maprooms to others.

Sixty people just like Assefa took part in the first round of trainings. After seeing the effectiveness and popularity of the course, the Ministry of Agriculture has promised to support many more. By the end of 2020, Dinku hopes at least 5,000 additional agronomists and agriculture extension agents will be trained to use the new tools and to pass that knowledge on to more of their peers.

“There are 60,000 extension workers in Ethiopia – these are the people who advise and support farmers directly, and who farmers trust. I believe ACToday can reach every one of them,” Dinku said.

Farming Communities in Guatemala Get Unprecedented Access to Climate Services

Sustainable Development Goal 2 is to end hunger and malnutrition and double the agricultural productivity of smallholder farmers by 2030–an ambitious set of targets made more so because of climate variability and change. National governments are working hard to enact and manage policies to help them meet SDG2. However, the success of these policies largely depends on how effectively they can reach millions of smallholder farmers who are trying to grow crops without irrigation. Their livelihoods depend on having a favorable climate during their growing seasons. Droughts and extreme weather events can often spell disaster for these communities, who generally don’t have access to reliable forecasts, warnings and other advisories to help them plan for and avoid the worst outcomes.

For this reason, ACToday has been working closely with national climate institutions in each of its six countries not only to improve the quality of their forecasts and advisories, but also to ensure that as many people as possible have access to these new products.

One of our biggest successes has been in Guatemala, where chronic malnutrition rates are the fourth-highest in the world and the highest in Latin America and the Caribbean, and where the poorest communities have recently faced multi-year droughts.

In the spring of 2019, ACToday helped launch five new information-sharing roundtables across the country designed to give farmers unprecedented access to state-of-the-art climate information, products and tools that they need to increase crop productivity and improve food security (see map).

The roundtables, or mesas técnicas agroclimáticas (MTAs), build on an existing model in Guatemala by the CGIAR Research Program on Climate, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), an ACToday partner.

Through these roundtables, ACToday is able to work with community leaders to bring together farmers and other stakeholders to regularly review recent climate conditions, share the latest forecasts, and recommend actions for communities to take. It’s a mechanism that gives thousands of marginalized growers across Guatemala a venue in which to voice their needs and concerns, directly or through representatives and intermediaries.

“Now farmers can communicate directly with their government, and their government can learn directly from farmers about the challenges they face, and what tools might help them solve those challenges”, said Juan Pablo Oliva, director of INSIVUMEH, Guatemala’s national meteorological agency, and ACToday partner.

For example, the roundtables in the regions of Totonicapán and Quetzaltenango focus on reaching indigenous communities, who, due to barriers of language and geography, often face particularly high hurdles in accessing relevant climate information. “We want our forecasts to make it to these farmers, in their local languages, so they can incorporate the information into their agricultural calendars,” said ACToday’s Diego Pons, who is from Guatemala. “Historically, they’ve been left out of the loop.”

We want our forecasts to make it to these farmers, in their local languages, so they can incorporate the information into their agricultural calendars. Historically, they’ve been left out of the loop.

Diego Pons

The roundtables are a way of correcting this. By tapping into the best climate information available to help decide what to plant and when to plant it, these communities can take more control over their own livelihoods.

“Our hope is that we’ll see incomes rise, more kids staying in school, and more Guatemalans staying on their land,” Pons said.

Another roundtable, in the south-central region, addresses the needs of Guatemala’s coffee producers. Coffee is one of the most important cash crops in the country, and 96% of it is grown by small producers who have less than three hectares of land, said Mariela Meléndez of Anacafé, the country’s national coffee association.

“Many smallholder coffee producers will also grow corn or beans next to their coffee plantations to provide food for their families. Income from coffee helps these families give their children access to education, improve their quality of life and climb out of extreme poverty,” she said.

MTAs are a crucial part of creating sustainable feedback loops between stakeholders and users of climate information.

“The roundtables constitute an excellent example of farmers, government agencies and international organizations working together to effectively embed the best possible climate knowledge into actual decisions,” said ACToday co-director, Walter Baethgen. “This is an example of the “culture” that ACToday is trying to build in the routine work of governments and development agencies.”

A New Climate Academy in Bangladesh

While one ACToday team was working to organize information-sharing roundtables for Guatemala’s farming communities, another team was busy 10,000 miles away, developing an altogether different model to connect climate information providers and decision makers.

The Bangladesh Academy for Climate Services (BACS), launched in summer 2018, was the first of its kind in the country. Based at the Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB), the new academy offers climate trainings and resources to professionals working in agriculture, food policy, disaster preparedness, public health and other fields. It also provides a platform to connect producers and users of climate information and improve coordination of efforts in the climate services space.

ACToday/IRI hosted a training in New York with support from Climate Services for Resilient Development and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in March of 2018.

Bangladesh may be one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change, but it is also where almost everyone—all the way to the smallest communities—is aware of climate thanks to massive awareness-raising campaigns and adaptation initiatives.

Saleemul Huq, ICCCAD

“Bangladesh may be one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change, but it is also where almost everyone–all the way to the smallest communities–is aware of climate thanks to massive awareness-raising campaigns and adaptation initiatives,” said Saleemul Huq, director of the International Center for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD). However, climate thinking still needs to be better integrated into all sectors of Bangladesh’s economy, Huq said, which is why ICCCAD was eager to partner with ACToday, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and the Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) to launch BACS.

“There is a gap in understanding and communication between climate scientists, policy planners, development and extension organizations, and downstream users of climate information,” said Ziaul Islam, from Bangladesh’s Ministry of Planning, who took the very first BACS course.

Addressing this gap, and improving climate services overall in Bangladesh will help improve the scale and efficiency of adaptation projects, particularly with respect to agriculture, food security and nutrition. Nearly a quarter of Bangladeshis–40 million people–are food insecure, and 11 million suffer from acute hunger.

By the end of 2019, BACS will have trained approximately 40 professionals, with additional courses planned for 2020. The trainings enable decision makers like Islam to get a deeper understanding about how climate can impact their sectors and their projects, and how to take advantage of data tools, forecasts and other products developed by national agencies.

Climate Risk Insurance for Colombia’s Smallholder Rice Farmers

The work we’ve shared in the previous sections highlight ways that ACToday has helped create advanced and sustainable climate services tailored for agricultural decision making. Countries are using these new services to manage many of the climate-related risks to their food systems. However, even the best climate services by themselves cannot manage the entire range of climate risks that farmers confront. Farmers in the United States and other developed countries are able to cover some of the remaining risks through traditional insurance. If their crops are destroyed by a drought or a storm, they can file a damage claim with the insurance company, which would then send out an assessor to verify and quantify the damages. However, in the six ACToday countries—and most other developing countries—such a system becomes prohibitively expensive for companies, and ultimately makes premiums unaffordable to the rural smallholder farmers who most need insurance.

To address this challenge, IRI has been one of the pioneers to develop a new type of insurance called index insurance. Index insurance payouts are based on an index of weather, such as rainfall measured by satellites or at a local weather station. If the amount of rainfall during critical stages of a crop’s growth cycle doesn’t reach a pre-specified threshold, farmers automatically get compensated without having to file any claims. This innovation has significantly lowered the transaction costs and risks for insurance companies, enabling them to keep premiums low and enabling millions of farmers access to coverage previously unavailable to them.

Index insurance is a key component of ACToday’s work in all six countries, and teams have been working with government and private sector partners to design products tailored to the needs of each country. One of our earliest and most committed partners has been Fedearroz, the rice producers’ federation of Colombia.

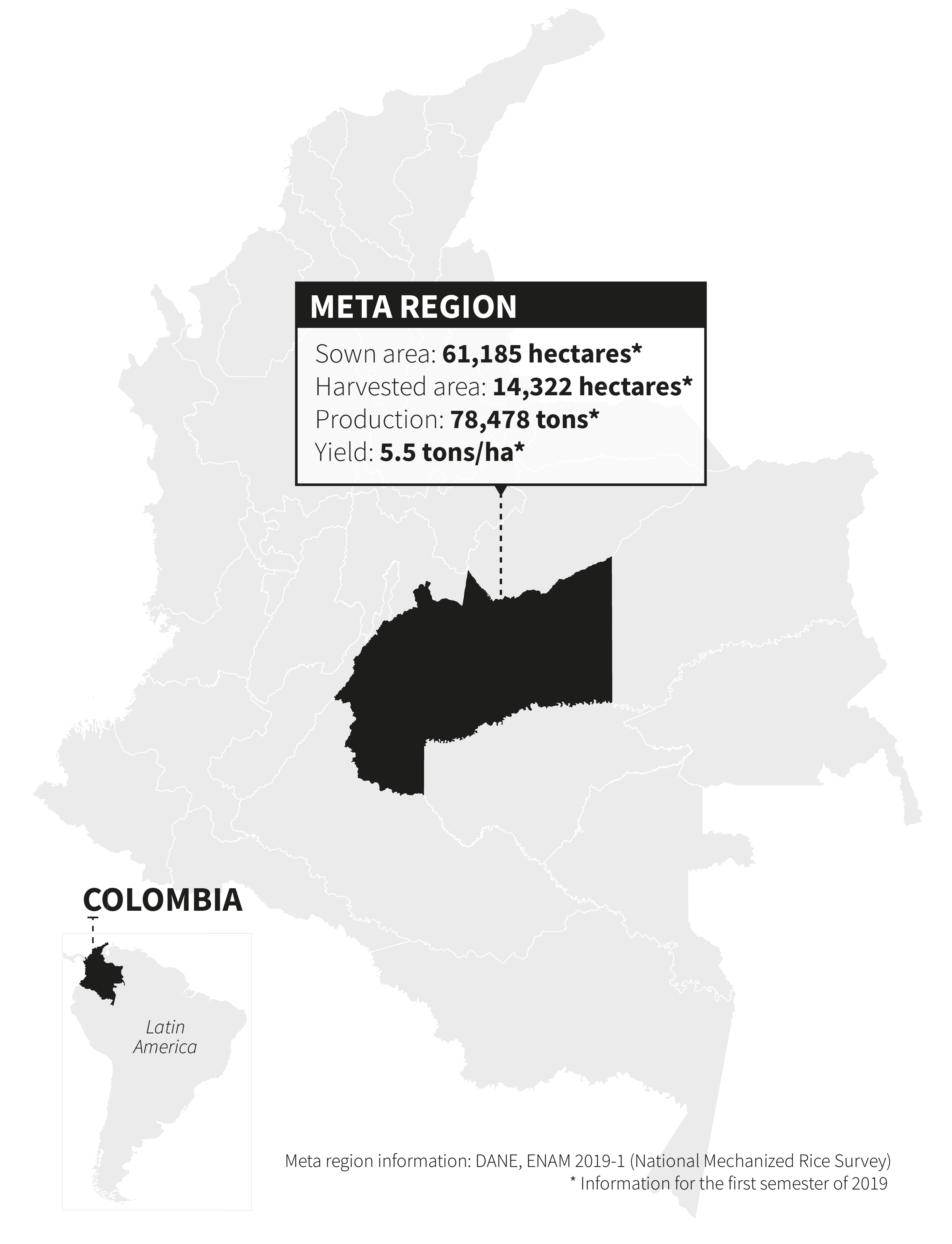

Fedearroz represents the country’s 28,000 rice farmers, which together harvest more than 2.5 million tons of the crop each year. Rice is one of the key basic staple foods in Colombia. On average, Colombians consume more than 66 lbs (30 kg) of rice per person per year.

“The support of ACToday to our index-based insurance pilot is crucial to our plans to implement climate-smart rice production in Colombia, contributing to increased food security in our country,” said Patricia Guzman, the deputy director of technology at Fedearroz.

With ACToday technical and training support, Fedearroz will launch a pilot insurance project in March of 2020 for 100 farmers in the Meta region, which produces a sixth of all the rice in Colombia.

“Rice is an extremely important crop for Colombia’s food security, and farmers face constant climate risks, from drought to excessive rainfall, that can damage or destroy crops and reduce income,” said ACToday’s Manuel Brahm, part of the project’s Colombia team.

Brahm and others on the team have been training and supporting Fedearroz staff to design index insurance products that will protect their farmers against climate-related crop losses. ACToday and Fedearroz have held multiple workshops with rice farmers there to understand local perspectives and needs.

“They’ve helped us understand which stages of the rice growing cycle they feel are most vulnerable to damage from too much or too little rainfall, which allows us to define a coverage window for the insurance product,” Brahm said. “We also asked them to rank years from best to worst in terms of yields, and we can compare this in real time to what the climate data says using IRI’s Data Library.”

This information feeds into the design of the insurance and helps ensure that companies will be able to provide an affordable product that covers as much risk as possible for the greatest number of farmers.

ACToday is catalyzing a very favorable institutional landscape in Colombia, promoting the development of complementary capacities in different productive sectors, so we can take full advantage of the opportunities that climate offers to us.

Patricia Guzman, Fedearroz

“Our experience shows that a top-down approach—where scientists or government agencies decide what insurance communities need—doesn’t work in the long term and doesn’t scale up as quickly,” said economist Daniel Osgood, who leads IRI’s Financial Instruments Sector Team. “ACToday is designing index insurance through a participatory process that has involved farmers from the very beginning—they’re the ones who will be deciding whether or not to buy coverage.”

ACToday’s approach has been to train and support the Fedearroz staff to develop the index insurance in-house. This leaves the association with the technical capacity and experience to scale up to more farmers over time. It can also serve as a model for other associations, such as coffee growers, to build on.