Adapting Agriculture to Climate Today, for Tomorrow (ACToday) is a Columbia World Project led by the International Research Institute for Climate and Society. The project aims to combat hunger and improve food security by increasing climate knowledge in six countries that are particularly dependent on agriculture and vulnerable to the effects of climate change and fluctuations: Bangladesh, Colombia, Ethiopia, Senegal, Vietnam and Guatemala. This article takes an in-depth look at a new series of roundtables launched in Guatemala to advance ACToday’s goals.

By Elisabeth Gawthrop

Thousands of Guatemalan farmers will now have access to state-of-the-art forecasts and other climate information to help them increase crop yields and earn more, thanks to five new regional collaborative networks launched by Columbia University’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society and its international and Guatemalan partners.

Key Partners

International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI)

CGIAR Research Program on Climate Climate, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS)

International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT)

National Institute for Seismology, Volcanology, Meteorology and Hydrology (INSIVUMEH)

Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food

World Food Program (WFP)

The collaborations are called mesas técnicas agroclimáticas, or agroclimatic roundtables, abbreviated as MTAs. They comprise experts and decision makers ranging from small farmers to representatives from a wide variety of institutions, including local municipalities, national government, humanitarian agencies, farmers associations and international organizations. The representatives meet regularly to discuss recent climate conditions and the latest forecasts. They then agree on a set of good agricultural practices for the region, as well as strategies to communicate those recommendations.

MTAs are a key component of IRI’s work in both Guatemala and Colombia for Adapting Agriculture to Climate Today, for Tomorrow (ACToday), the Columbia World Project it leads. The goal of ACToday is to use climate science and services, including state-of-the-art forecasting tools, to help Guatemala and five other countries combat hunger and improve food security.

“It’s important we don’t underestimate the tangible difference these roundtables will make in people’s lives,” said IRI’s Walter Baethgen, who co-leads the ACToday project. “We are ensuring that the best climate information Guatemala produces is not only directly making its way to underserved communities, but that the communities have a say in what information gets produced, based on the needs of their growers.”

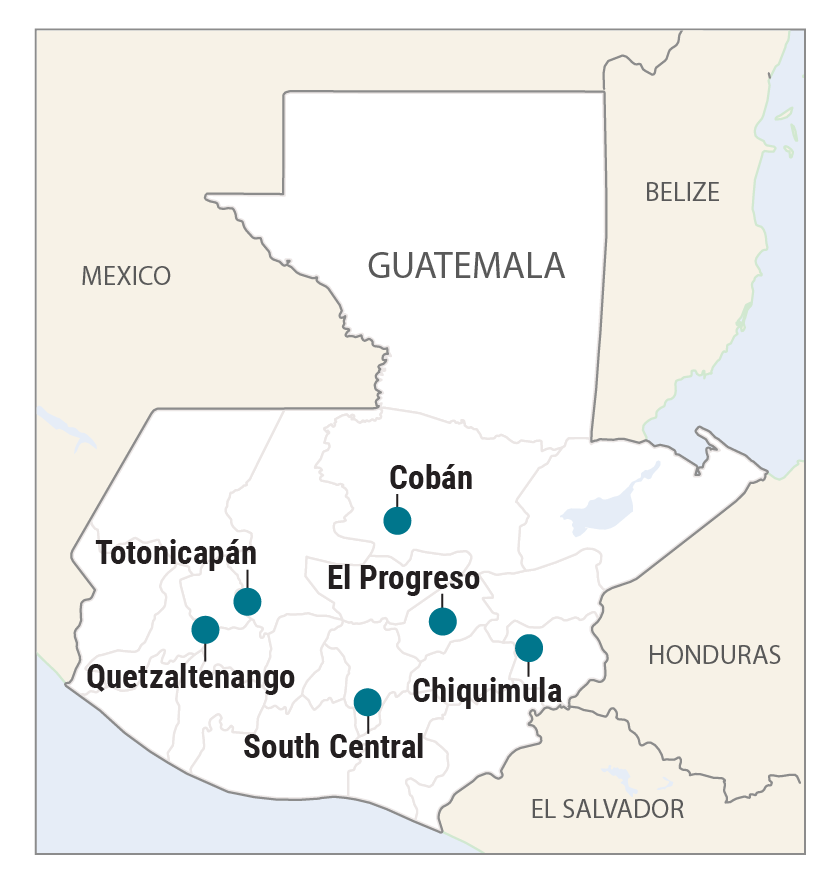

The five new MTAs are located throughout Guatemala: from the highlands in the west, to the lowlands in the south, to middle elevations in the northern and eastern parts of the country (see map). They build off an existing MTA launched in Chiquimula as part of AgroClimas, a CIAT/CCAFS project that continues to co-develop the MTAs with ACToday and the other partners. Taken together, these new networks will ensure that tens of thousands of farmers not only have access to important climate information and advisories, but have a way to voice their needs and give feedback to Guatemala’s national meteorological service (INSIVUMEH), which produces such information.

Forecasts for Food Systems

Like in many countries that rely on agriculture economically, many Guatemalans struggle to eat enough food. Chronic malnutrition rates are the fourth-highest in the world and the highest in Latin America and the Caribbean. Around one million farmers in the country are subsistence farmers, many living in areas exposed to climate shocks and without access to irrigation. Even for farmers that have irrigation, severe droughts and floods remain real risks.

Climate information can’t prevent droughts and floods from happening, but a better understanding of the past, present and future climate in a farmer’s region can help that farmer make better-informed decisions. A core value of the MTA process is that the development and delivery of the climate services has to be done with the participation of people all along the value chain of climate information, including to the level of the subsistence farmer.

“National agencies spend a lot of time and effort to improve their ability to observe and forecast climate and weather changes,” said IRI’s Diego Pons. “Often, these advances are either not reaching or not being utilized by the most vulnerable communities, because up until now there hasn’t been a process in place to facilitate this.”

Pons, a postdoctoral research scientist who has conducted field work in Guatemala for more than 10 years, is working to change that by leading ACToday’s work on MTAs in Guatemala. He is encouraged by the positive response to the MTAs from local and national institutions, with high level officials attending the launches of the MTAs and active participation at the events.

“We’re excited that we can have a direct impact on the population. This is something that really gets us up and out of bed every morning.”

Juan Pablo Oliva Hernández, Director of Guatemala’s national meteorological service (INSIVUMEH)

While all of the MTAs follow a similar process, each are designed to respond to local needs. In Guatemala, each region grows different food and has a unique climate.

In the highlands, people rely on the food they grow for their own meals, and they earn some money from selling food at local markets. Farm plots are generally small, ranging from 0.5 to 2 hectares. Water is piped from mountaintops in some areas, while other areas rely only on the rainfall that falls locally. Crops include staples such as maize and beans—often grown using a traditional system called milpa—as well as an array of fruits, vegetables and herbs.

Community structures, networks and ways of communicating also vary throughout the country. For example, the Asociación de Cooperación para el Desarrollo Rural de Occidente, a regional farmers association abbreviated CDRO, has been critical for setting up the new highlands MTAs in Totonicapán and Quetzaltenango.

“We identified CDRO as a partner because it already has a climate monitoring system and they already have surpassed many of the barriers that kept farmers from getting information. For example, they use local languages and incorporate traditional knowledge in their communications,” said Pons. He and the rest of the ACToday team are learning about the traditional knowledge and indicators that some farmers use for their planning and planting.

“We can now include these traditional perspectives in the forecasts we provide,” said Pons.

In Guatemala’s south-central region, the needs and climate challenges of growers are different in a number of ways. Here, much of the land is used to grow coffee and sugar cane, usually on large farms that provide seasonal work and cash for some farmers. Anacafé, the country’s national coffee association, was a natural partner in setting up an MTA in this region.

Mariela Meléndez, who works for Anacafé and coordinates the new south-central MTA, said 96% of Guatemalan coffee is owned by small producers with less than 3 hectares. Coffee cultivation represents the largest agroforestry system in Guatemala, with an area of 305,000 hectares.

“Many small coffee producers will also grow corn or beans next to their coffee plantation, to provide food for their families,” she said. “Coffee, as a cash crop, helps these families provide their children with access to education, improve their quality of life and get out of extreme poverty.”

Communication is Key

Farmers in the south-central region have access to climate information via a coffee smartphone app that already delivers El Niño forecasts from IRI. Any new and improved information ACToday helps generate can easily get conveyed to decision makers through this app.

Go in-depth with the details and science behind the MTA process: read the paper and training manual from our partners at CCAFS and CIAT.

But even with more advanced technology, communicating between people with very different professional and education backgrounds is still difficult.

“The hardest part of climate services is not only generating information that wasn’t there before, but how to get that information to communities in a way they understand and can use on the ground,” said Pons.

The MTA leaders utilize intentional, participatory exercises designed to help facilitate knowledge sharing. These exercises are particularly critical for understanding when climate information could be useful for decisions at the farm level, and the best ways of communicating climate information.

The participative spirit also extends to the managerial level of the MTAs. In a democratic process at the launch of the south-central MTA, each member of the committee wrote down their ideas for a mission and vision statement. Then all were read aloud and discussed before arriving at the agreed-upon, high level statements. The launch also included an exercise to crowd-source the attendees’ knowledge on climate data availability throughout the region.

INSIVUMEH also recognizes the need for improved communication of climate information. “Now that the science has advanced, a process of translation is needed and that is where the MTAs come to serve their purpose,” said Juan Pablo Oliva Hernández, the director of INSIVUMEH. “The MTAs can bring these products to the regions. We’re excited that we can have a direct impact on the population. This is something that really gets us up and out of bed every morning,” said Oliva Hernández.

More on the new MTAs from our partners:

For more on ACToday at IRI visit iri.columbia.edu/actoday. All photos and graphics are by Elisabeth Gawthrop unless otherwise noted.